Widely recognised as the cradle of winegrowing, Georgia is also a bridge between Europe and Asia. Its idiosyncratic winemaking traditions, myriad grape varieties and long standing wine culture have allowed its wine industry to overcome some major challenges in recent decades. Consultant winemaker Giorgi Samanishvili demonstrated Georgia’s ability to make wines that run the gamut in terms of styles, giving it the kind of broad-ranging appeal that will help it rise to future challenges.

Report : Sharon Nagel – at the 3rd Asian wine and spirits Symposium & Tasting

Georgians take great pride in emphasising their long-standing history of making wine and the many rituals that accompany both its production and consumption. Over its 8,000 vintages, Georgia has developed an intricate network of vineyard sites into which a comprehensive varietal range, to say the least, is deftly woven. Each of its 10 wine regions boasts its own array of grape varieties, borrowed from a nationwide collection of over 500 endemic vine types. The country’s complex topography and geography, shaped amongst other things by its 26,000 rivers, its location between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus mountains to the North, have produced a mosaic of micro-zones that can provide a suitable home for the 30-50 most widely grown grapes, including the country’s standard bearer, Saperavi. Its much-lauded ‘qvevri’ technique of making wine underground in terracotta amphorae is protected by Unesco and gives rise to a unique amber wine offering up truly authentic flavours. These, along with modern-day winemaking methods, are used by Georgia’s 800 wine companies, 300 of them exporters. They produce between 120 and 150 million litres of wine annually from a total area under vine of 50,000 hectares, spread across the entire country, with the exception of the mountains where conditions are too hostile for growing vines.

Wine styles to please all palates

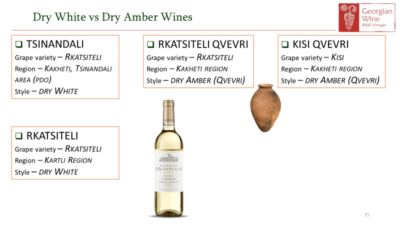

From the extensive range of wines available, Giorgi Samanishvili chose to illustrate the diversity of regional styles whilst extolling the merits of qvevri wines. Georgia is home to around twenty protected designations of origin, one of which – Tsinandali – was showcased through a blend of Rkatsiteli and Mtsvane, producing a classic dry white wine. The same Rkatsiteli grape made in qvevris yielded a dry amber wine with balanced alcohol, acidity and tannins. “Many qvevri wines are bottled in the summer before the next harvest, most are organic and not filtered or treated before bottling because the wines have more protective compounds and are more stable”, explained Samanishvili. Three renditions of the Saperavi grape variety confirmed Georgians’ preference for tannic wines, though the Saperavi Mukuzani is also one of Georgia’s most popular exports. The third Saperavi from Kindzmarauli, revealed the varietal’s versatility – with 40g of residual sugar, it is a naturally sweet red wine with an ABV of 12%. Fermentation was originally stopped by the cold weather, but now refrigeration is used. Like many of its neighbours, Georgia is also a keen spirits producer and consumer and Samanishvili presented a traditional, pomace-based brandy, Fine Chacha.

Traditions are something Georgia is not lacking when it comes to drinking rituals. At a traditional banquet, or Supra, the toast master or Tamada proposes numerous toasts throughout the meal. The similarity with China’s ‘ganbei’ tradition is striking and yet again illustrates Georgia’s pivotal role between East and West.